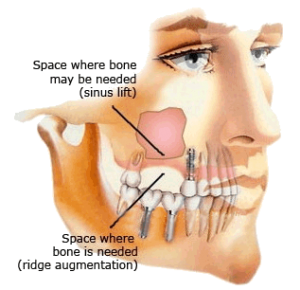

The status of the maxillary sinus and ostiomeatal complex should be determined endoscopically. Coronal computed tomography helps assess the status of the maxillary sinus and can identify retained dental roots and unerupted teeth. When evidence of obstruction of the sinus ostium is present, the planned procedure should include reestablishment of maxillary sinus drainage. If a palatal flap is planned, patients can be aided through fabrication of an acrylic splint that is fixed with clasps to the residual dentition for protection of the wound while it heals.

Surgical approaches

Closure of an oral-antral fistula consists of two procedures completed at the same setting. First, chronic sinusitis must be dealt with either by drainage through a nasoantral window and complete removal of the infected mucosa or by opening of the natural ostium.

Closure of an oral-antral fistula may be undertaken with the patient under either local anesthesia with intravenous sedation or general anesthesia. Local anesthesia may be achieved with a local field block, occasionally supplemented with lidocaine injected into the greater palatine foramen.

Necrotic bone and soft tissue must be removed. The status of the mucosa in the sinus is ascertained, and diseased or polypoid mucosa is removed if it is obstructing sinus drainage. The preferred technique is enlargement of the natural ostium. Epithelium bridging the defect from the oral cavity to the maxillary sinus must be removed, as well as infected or necrotic bone. At this point, either a sliding bipedicle flap or an advancement rotation flap should be developed from the adjacent buccal or palatal mucosa. The surgeon must plan the flap so that the gingivobuccal sulcus is not obliterated in patients who use dentures. Adequate length of the flap must be achieved to allow closure without tension. The flap is developed in a plane just superficial to the periosteum and rotated or advanced to close the oral-antral fistula. Either permanent sutures (e.g., silk) or long-lasting absorbable sutures (e.g., Vicryl) are used.

Mobilization and rotation of the palatal flap to cover the fistula. The resulting mucosal defect in the palate is allowed to granulate and heal by secondary intention. Most patients will be more comfortable if an acrylic splint is fabricated for use during eating.

We use an alternative technique for the management of oral-antral fistulas that develop after dental extractions . These fistula frequently arise directly on the alveolar ridge. Once again, it is necessary to débride necrotic bone and remove any diseased epithelium bridging the mucosa of the maxillary sinus with the alveolar ridge. This is facilitated by making an incision through the mucosa of the alveolar ridge parallel to the alveolar ridge. The necrotic bone is débrided superiorly until normal bone is identified to permit mobilization of the mucosal flaps for primary closure. With adequate débridement of bone, the mucosa of the alveolus can be closed directly over the fistula site.

Postoperative menagement

Two to 3 weeks of healing is required to achieve adequate wound strength to withstand the trauma of mastication. The use of a dental prosthesis (bridgework or dentures) and chewing are avoided during convalescence. If an acrylic splint is available to cover the palatal defect, most patients can begin to drink fluids the afternoon of surgery. Administration of an antibiotic effective against oral flora may be of some benefit. Patientsare instructed to eat a soft diet and chew on the contralateral side. The patient must clean the mouth and suture line with half-strength peroxide or Peridex after each meal for 6 weeks.

Failure to ensure adequate drainage of the maxillary sinus into the nasal cavity may result in a persistent oral-antral fistula. Effort must be made to ensure either that the natural ostium is patent or that a new nasal antrostomy has been created.

Failure to remove necrotic tissue, osteomyelitic bone, chronically infected antral mucosa, and epithelial bridges from the oral mucosa to the maxillary sinus may prevent healing and result in persistent infection and recurring fistula. These issues should be carefully addressed during surgery.

Development of a buccal or palatal flap of insufficient length or breadth may compromise healing because of a tight suture line and lead to a resultant recurrent fistula. Similarly, repair with absorbable sutures such as catgut or chromic catgut may be inadequate to ensure healing before dissolution of the suture material.

A recurrent oral-antral fistula after attempted surgical repair is usually a result of inadequate management of the sinusitis, which is frustrating to both the surgeon and patient. The literature abounds with techniques advocated for repair of chronic oral-antral fistulas, including the use of vascularized tissue such as buccal fat pad,a submental island flap,and palatal rotation. Some patients benefit from nonsurgical management with a prosthesis.